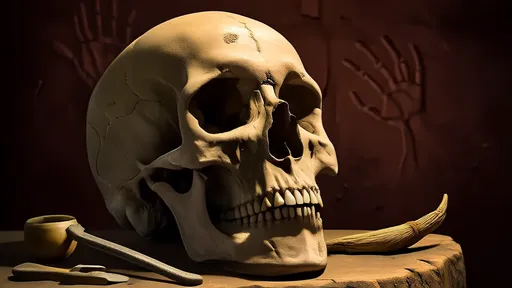

In the shadowy recesses of human prehistory, long before the advent of modern medicine, our ancestors performed a remarkable and daunting medical procedure: drilling or scraping a hole into the human skull. This practice, known as trepanation, represents one of the earliest forms of surgical intervention, with archaeological evidence tracing its roots back to the Neolithic period. The discovery of ancient skulls bearing precisely crafted holes, many showing clear signs of healing, has captivated anthropologists and medical historians for decades. It forces a profound reconsideration of the capabilities and sophistication of early human societies, suggesting a complex understanding of human anatomy, a willingness to intervene in cases of trauma or illness, and perhaps even a belief in spiritual or ritualistic healing.

The sheer prevalence of trepanned skulls found across the globe—from the plains of Europe and the mountains of Peru to the islands of the Pacific—indicates that this was not an isolated cultural anomaly but a widespread practice. The motivations behind such a drastic procedure remain a subject of intense debate. Some scholars posit that it was a pragmatic response to head injuries, intended to relieve pressure from skull fractures or hematomas. Others suggest it was a treatment for a range of ailments, from severe headaches and epilepsy to mental disorders, which ancient peoples might have attributed to evil spirits or supernatural forces trapped within the head. The ritualistic aspect cannot be ignored either; the removal of a piece of the skull may have been performed to create a permanent opening for spirits to enter or leave, or as part of an initiation rite.

What is perhaps most astonishing is not merely that the procedure was attempted, but that a significant number of patients survived it. Analysis of healing patterns on ancient crania provides a silent testimony to their ordeal and recovery. By examining the bone regrowth around the edges of the trepanation opening, osteoarchaeologists can distinguish between perimortem procedures (those performed at or near the time of death, often indicated by sharp, unhealed edges) and those where the individual lived for months or even years afterward. The latter show smooth, rounded edges where new bone has grown, a process called remodeling. The degree of this healing offers a rough timeline of survival post-operation.

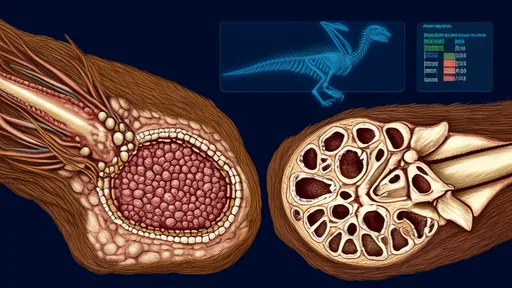

The success rate, inferred from these healing signs, is surprisingly high. In some studied collections, over half of the trepanned skulls show evidence of extensive healing. This suggests that the practitioners, whom we might call the first neurosurgeons, possessed not only considerable courage but also a non-trivial degree of skill and knowledge. They likely had an empirical understanding of which areas of the skull to avoid, such as the midline where the meningeal arteries are located, to prevent fatal bleeding. The tools used, primarily sharpened stones of flint or obsidian, were crafted with precision. The techniques varied, including scraping, grooving, drilling, and boring-and-cutting, each requiring a steady hand and intimate knowledge of cranial thickness.

Furthermore, post-operative care must have been a critical component of survival. The open wound would have been highly susceptible to infection. It is plausible that ancient healers applied poultices made from plants with known antibacterial or anti-inflammatory properties, though such evidence is lost to time. The survival of these patients indicates a community effort, where the individual was nursed and protected during a vulnerable recovery period, hinting at a complex social structure capable of supporting its injured and ill members.

The study of these ancient cases is not merely an academic exercise in archaeology. It provides a deep, historical context for modern neurosurgery and our understanding of human resilience. It challenges the simplistic notion of prehistoric life as a constant struggle for survival, instead revealing a picture of innovation, care, and sophisticated empirical knowledge. Each healed trepanation is a story of individual suffering, bravery, and community, etched into bone—a permanent record of humanity's enduring quest to heal itself against all odds.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025