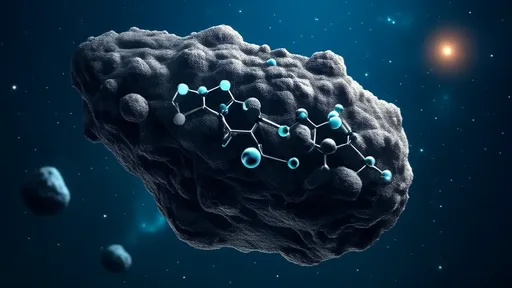

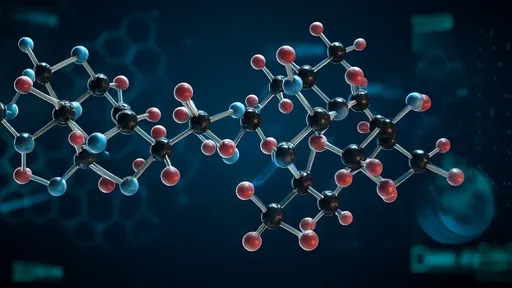

The discovery of amino acids on meteorites has long tantalized scientists with the possibility that the building blocks of life may have been delivered to Earth from space. But one of the most profound implications of this extraterrestrial connection lies in a subtle molecular asymmetry—a phenomenon known as chirality. Organic molecules can exist in two mirror-image forms, much like left and right hands. Yet life on Earth exclusively uses left-handed amino acids and right-handed sugars. This preference, called homochirality, is a fundamental and unresolved mystery in the origin of life. Recent analyses of carbonaceous chondrites—primitive meteorites that have fallen to Earth—are providing compelling evidence that this bias might not have originated on our planet at all, but was instead imprinted by processes in the interstellar medium or the early solar system.

The Murchison meteorite, which fell in Australia in 1969, has been a treasure trove for prebiotic chemistry. Studies over decades have confirmed that it contains a rich array of amino acids. Crucially, measurements have shown an excess of left-handed (L-) amino acids over their right-handed (D-) counterparts. This excess is small, often only a few percent, but it is significant and has been replicated in analyses of other meteorites like the Murray and Orgueil. The consistency of this finding across different falls suggests it is not contamination from terrestrial biology, but an inherent property of the organic material formed in space.

So, how does this asymmetry arise in the cold vacuum of space? One leading hypothesis points to circularly polarized light (CPL) emanating from neutron stars or other astrophysical sources. As this light travels through vast molecular clouds, its helical nature can selectively break down one enantiomeric form of a molecule over the other, creating a small but persistent imbalance. Laboratory experiments have successfully used CPL to induce such enantiomeric excesses in simulated interstellar ices, providing a plausible physical mechanism for the bias observed in meteorites. Another proposed mechanism involves magnetized protostellar nebulae, where spin-polarized electrons could influence the formation of chiral molecules, favoring one hand over the other.

The journey of these organics from a molecular cloud to a planet like Earth is a long and violent one, involving the collapse of a cloud into a protoplanetary disk, the accretion of planetesimals, and the eventual delivery via meteorites. The fact that the chiral excess survives this process is remarkable. It suggests that the bias is not a fragile quirk but a robust feature, perhaps even amplified by aqueous alteration within the parent asteroids of these meteorites. Water, percolating through the rock, could have further enriched the left-handed amino acids through processes like crystallization and dissolution, setting the stage for a prebiotic world already predisposed toward a specific handedness.

The implications for the origin of life are staggering. Instead of a perfectly racemic (50/50) mixture of amino acids arriving on early Earth and then undergoing a random, difficult-to-explain transition to homochirality, the stage may have been pre-set. The "seeds" of life's handedness, the initial push away from symmetry, could have been extraterrestrial. This doesn't simplify the entire puzzle—how this small excess was amplified to the near-100% homogeneity seen in biology is still a major area of research—but it provides a crucial starting point. It suggests that the path to life as we know it was not entirely random but was guided, at least in its initial conditions, by the astrophysical environment of our nascent solar system.

This research forces a profound shift in perspective. Life on Earth is often studied as a closed system, but these findings underscore that our planet is part of a much larger cosmic ecosystem. The materials and even the molecular biases that led to our existence were forged in space. This connects the specific chemical narrative of life on Earth to universal astrophysical processes. If chiral biases are a common outcome of star and planet formation, then the initial conditions for life might be widespread throughout the galaxy. The universe, it seems, might have a inherent leaning toward the left-handed.

Future missions and analytical techniques are poised to deepen this investigation. The return of samples from asteroids like Ryugu by JAXA's Hayabusa2 and Bennu by NASA's OSIRIS-REx provides pristine material, completely untainted by Earth's environment, for chiral analysis. Space telescopes are also getting better at detecting the spectroscopic signatures of chiral molecules in interstellar clouds. Finding such an imbalance in situ, far from any planet, would be the ultimate validation of the cosmic origin of life's handedness.

The discovery of a left-handed bias in meteoritic amino acids is more than just a curious chemical detail. It is a tangible piece of evidence pointing to an extraterrestrial influence on one of life's most fundamental characteristics. It suggests that the origins of life are deeply intertwined with the processes of cosmic evolution, from the formation of stars to the dynamics of protoplanetary disks. As we continue to explore our solar system and beyond, this cosmic handedness may well prove to be a universal signature, a silent directive from the universe itself, guiding matter toward complexity and, ultimately, life.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025