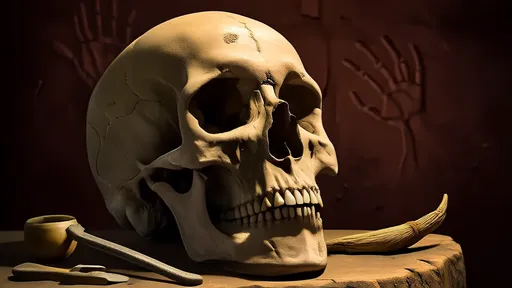

In the hushed halls of museums and the silent depths of archaeological sites, the physical remnants of ancient civilizations have long told a story of visual and tactile artistry. We can see the intricate carvings, feel the weight of a stone tool, and marvel at the craftsmanship of a gold funerary mask. Yet, for all these sensory experiences, one profound dimension of ancient life has remained stubbornly silent: its sound. The music, the chants, the very acoustic atmosphere of sacred and social spaces were thought to be lost to time, ephemeral vibrations that faded into nothingness centuries ago. This historical silence, however, is being shattered by a revolutionary new field known as acoustic archaeology.

Acoustic archaeology is an interdisciplinary endeavor that merges the meticulous methods of traditional archaeology with cutting-edge audio engineering, 3D scanning, and computer modeling. Its primary mission is to reconstruct the sonic environments of the past. While the study of ancient instruments (organology) has been around for some time, acoustic archaeology expands this focus exponentially. It is not merely about determining what a single lyre or conch shell trumpet might have sounded like in isolation. The field's most ambitious and transformative project is the three-dimensional digital reconstruction of entire ancient soundscapes and the precise acoustic fields of musical instruments. This process allows researchers to virtually "play" an instrument that may have been fragments for a millennium or "stand" in the center of a Neolithic stone circle and experience its unique auditory properties.

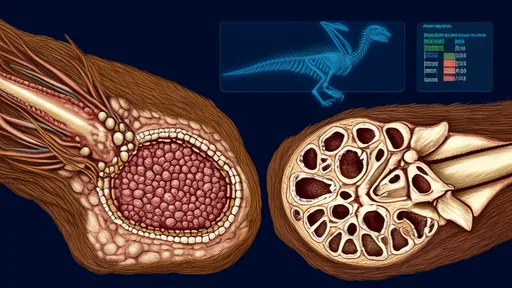

The journey of digital reconstruction begins not in a sound studio, but at the archaeological site or museum collection. The subject—be it a complete instrument, a fragment, or an architectural space like a temple or theater—is first captured in immaculate detail using 3D laser scanning or photogrammetry. These technologies create a hyper-accurate point-cloud model, a digital twin that captures every crack, curvature, and internal volume of the object or site. This geometric accuracy is paramount, as the shape and surface texture are the fundamental determinants of how sound waves are generated and propagate.

Once the precise digital geometry is established, the data is imported into specialized acoustic simulation software. These programs, often developed for architectural acoustics and automotive design, use complex algorithms based on the principles of wave equation physics to simulate how sound behaves within a defined space. For an instrument, researchers must define a virtual excitation point—the equivalent of a plucked string, a struck surface, or a column of air from a player's lips. The software then calculates the resulting vibrations across the entire structure, modeling the radiation of sound waves into the surrounding virtual space. The material properties of the original object—whether it was dense hardwood, brittle clay, or cold bronze—are assigned based on archaeological analysis, as these properties dramatically affect the damping, resonance, and timbre of the sound produced.

The output of this computationally intensive process is a impulse response and a detailed auralization. In simpler terms, it generates a unique sonic fingerprint for that instrument or space. This fingerprint can then be applied to a dry, anechoic recording of a modern musician playing a similar instrument, effectively placing that performance inside the ancient artifact. The result is not a synthetic guess but a scientifically-grounded auditory recreation of the instrument's voice. One can hear the bright, sharp attack of a Lur, a Bronze Age Nordic brass instrument, or the complex, warm harmonics of a meticulously reconstructed Greek kithara, exactly as its vibrations would have interacted with its own body.

The implications of this work are profound, stretching far beyond mere technical achievement. For musicologists and historians, it provides the first opportunity for true critical listening. They can now analyze the musical capabilities of ancient instruments with empirical data. Could this trumpet produce a harmonic series capable of playing a melody? Does the design of this drum suggest it was used for communication over long distances or for ritual trance ceremonies? The sound itself becomes a primary source, a new text to be read and interpreted.

Perhaps even more captivating is the application to architectural spaces. By creating 3D models of sites like the Greek theater of Epidaurus or the underground Mithraic temples of Rome, researchers can analyze their acoustic properties with scientific rigor. They can test long-held theories about why certain spaces were designed the way they were. The famed whisper-quality acoustics of Epidaurus can be quantified and understood not as myth but as physics. Similarly, the disorienting, reverberant, and intensely intimate soundscape of a Mithraeum can be experienced, offering a visceral understanding of how sound was used to enhance mystical religious experience. This allows archaeologists to move from asking "What did this place look like?" to "What did it feel like to be here?"—adding a deeply human layer to our understanding of the past.

Furthermore, this technology offers a powerful tool for digital conservation and restoration. For instruments too fragile to be played or handled, a perfect digital surrogate can be created and "played" indefinitely. This ensures that even if the original artifact succumbs to time, its sonic identity is preserved for future generations. It also allows for virtual restoration; missing pieces of an instrument can be digitally sculpted based on historical evidence, and their acoustic contribution to the whole can be tested and refined in the model before any physical restoration is ever attempted.

Of course, this pioneering field is not without its challenges and philosophical debates. The process requires making informed assumptions about material properties that can only be inferred after centuries of decay and patination. Was the leather of that drumhead tighter? Was the bronze alloy of that bell slightly different? Every assumption introduces a margin of error. Furthermore, scholars debate the very nature of the reconstructions. Are we hearing the "authentic" sound of the past, or a best-guess simulation? Most acoustic archaeologists posit that they are creating a plausible and scientifically-informed model, a powerful hypothesis that can be tested and refined as new data emerges, rather than a definitive truth.

In conclusion, the 3D digital reconstruction of ancient sonic environments is more than a technical marvel; it is a paradigm shift in historical inquiry. It reanimates a dimension of human experience that was thought to be forever lost. By giving voice to silent artifacts and breathing sound back into ruined spaces, acoustic archaeology allows us to engage with history in a more holistic and emotionally resonant way. We are no longer distant observers of the past but are invited, through headphones and speakers, to step inside its soundscape and listen, finally, to the echoes of a world we thought had fallen silent.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025