In the intricate landscape of cancer research, the mechanical properties of cells have emerged as a pivotal frontier in understanding tumor progression and metastasis. Recent breakthroughs in mapping cellular mechanics have unveiled a complex stress transmission network that tumors exploit to facilitate their spread. This mechanical interplay, once overshadowed by biochemical signaling, is now recognized as a critical driver of metastatic efficiency, offering new perspectives on how physical forces shape pathological behavior.

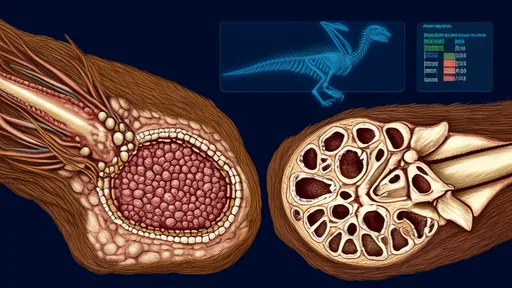

The concept of a cellular mechanical atlas refers to the comprehensive mapping of forces and mechanical properties within and between cells. In the context of cancer, this atlas reveals how tumor cells manipulate their mechanical environment to initiate migration and invasion. Unlike normal cells, cancer cells exhibit altered stiffness, enhanced contractility, and an ability to perceive and generate forces that favor disruption of tissue architecture. These mechanical changes are not passive consequences but active participants in the metastatic cascade.

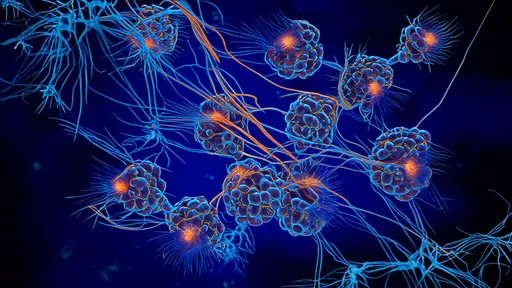

Central to this process is the stress transmission network, a dynamic system through which mechanical forces are propagated across cellular structures and into the extracellular matrix. Tumor cells leverage this network to sense stiffness gradients, align with stress patterns, and coordinate collective migration. Integrins, focal adhesions, and cytoskeletal components act as conduits for force transmission, converting physical cues into biochemical signals that reinforce invasive behavior. This mechanotransduction loop ensures that cells not only respond to their environment but also remodel it to support metastasis.

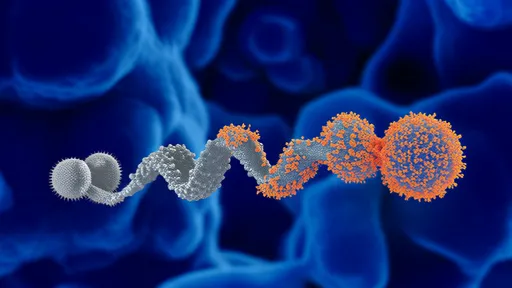

One of the most compelling aspects of this mechanical network is its role in collective cell migration. Metastasis often involves the movement of cell clusters rather than individual cells, and mechanical forces are essential for maintaining group cohesion and directionality. Through adherens junctions and gap junctions, mechanical stresses are communicated between cells, enabling synchronized movement and enhancing survival in circulation. This collective strategy increases the likelihood of successful extravasation and colonization at distant sites.

The extracellular matrix (ECM) serves as both a source and sink of mechanical stresses in this network. Tumors frequently stiffen the ECM through increased cross-linking and fiber alignment, creating pathways that guide cell migration. Simultaneously, cancer cells secrete enzymes that degrade the matrix, reducing physical barriers and generating traction forces that propel movement. This dual manipulation of the ECM exemplifies how tumors engineer their mechanical microenvironment to support dissemination.

Emerging technologies such as traction force microscopy and atomic force microscopy have been instrumental in decoding these mechanical interactions. These tools allow researchers to quantify forces at the cellular and subcellular levels, providing unprecedented insights into how stresses are distributed and utilized during invasion. High-resolution imaging combined with computational modeling has further elucidated the spatial and temporal dynamics of stress propagation, highlighting patterns that correlate with metastatic potential.

Targeting the mechanical components of metastasis presents a promising therapeutic avenue. Drugs that disrupt force transmission machinery—such as inhibitors of myosin contractility or integrin function—are showing efficacy in preclinical models. Similarly, strategies aimed at normalizing matrix stiffness or blocking mechanosensitive signaling pathways could impair the tumor's ability to spread. These approaches complement traditional therapies by addressing the physical underpinnings of metastasis that are often overlooked.

Despite these advances, challenges remain in translating mechanical insights into clinical practice. The variability of mechanical properties across tumor types and individuals necessitates personalized assessment methods. Moreover, the dynamic nature of stress networks means that interventions must be timed precisely to counteract metastatic events. Ongoing research aims to develop non-invasive techniques for mapping tissue mechanics in patients, potentially enabling early detection of metastatic propensity.

The integration of mechanical atlas data with genomic and proteomic profiles is paving the way for a more holistic understanding of cancer. This multi-dimensional approach reveals how genetic mutations influence mechanical behavior and vice versa, creating feedback loops that drive progression. For instance, oncogenes can upregulate force-generating proteins, while mechanical stresses can activate oncogenic signaling, blurring the line between cause and effect.

In conclusion, the mechanical atlas of tumor cells has uncovered a sophisticated stress transmission network that is fundamental to metastasis. By mapping and manipulating these physical forces, researchers are developing new strategies to combat cancer spread. As our tools and models become more refined, the hope is that targeting the mechanics of metastasis will become a standard part of oncology, offering patients better outcomes through innovative treatments that address both the biological and physical dimensions of their disease.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025