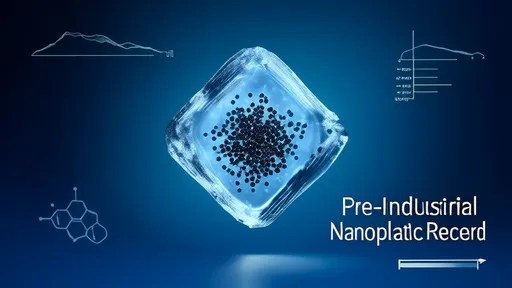

Scientists have recently turned to an unconventional source to understand the historical footprint of plastic pollution: ice cores drilled from remote glaciers. These frozen time capsules are revealing startling new evidence about the presence of nanoplastics in our atmosphere long before the modern plastic era, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of pre-industrial atmospheric baselines.

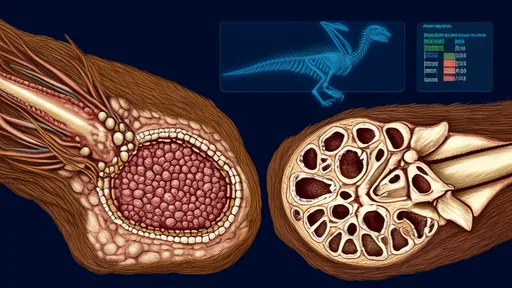

The research, led by interdisciplinary teams from glaciology, environmental science, and chemistry, involves painstaking analysis of ice core samples dating back centuries. Using advanced spectroscopic techniques and electron microscopy, researchers can now detect and characterize plastic particles as small as a few nanometers—particles so tiny they would have been invisible to previous generations of scientists. What they’ve found challenges the long-held assumption that plastic contamination is solely a post-20th century phenomenon.

Contrary to popular belief, nanoplastics did not suddenly appear with the mass production of plastics in the 1950s. The ice core record shows these microscopic particles were present in the atmosphere as early as the 18th century, coinciding with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. While concentrations were dramatically lower than today’s levels, their presence indicates that human activities—even before modern plastic production—were capable of generating and dispersing synthetic particles on a global scale.

The sources of these pre-industrial nanoplastics differ significantly from contemporary ones. Rather than degraded packaging or synthetic textiles, researchers point to early industrial processes. The burning of coal, which contains natural polymers, and early industrial activities involving rubber, lacquers, and treated materials likely generated these first anthropogenic nanoparticles. These particles then traveled through the atmosphere, eventually settling on remote ice sheets where they remained preserved in the accumulating snow layers.

This discovery has profound implications for how we define "natural" background levels of atmospheric pollution. For decades, scientists have used pre-industrial ice core measurements to establish baselines for various pollutants, from greenhouse gases to heavy metals. The presence of nanoplastics in these same layers suggests that even our cleanest historical benchmarks contain evidence of human impact. There is no true pre-human baseline for atmospheric purity—a sobering realization for environmental scientists.

The research methodology represents a triumph of analytical chemistry. Detecting nanoplastics in ice cores requires eliminating contemporary contamination while handling samples, a challenge that necessitated the development of clean-room procedures in polar environments. Scientists must work in positive-pressure laboratories wearing non-synthetic clothing to avoid introducing modern plastics to the ancient ice. The extraction process involves melting the ice under controlled conditions and filtering the meltwater through progressively finer membranes before analysis with Raman microscopy and pyrolysis-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.

What emerges from this technological tour de force is a detailed chronology of nanoplastic pollution. The ice core layers show a dramatic increase in nanoplastic concentration beginning in the 1950s, corresponding with the global expansion of plastic production. However, the pre-1950s layers tell a more nuanced story, with noticeable spikes during periods of intensive industrialization and warfare, when industrial activity and material innovation accelerated without environmental considerations.

The global distribution of these historical nanoplastics is equally revealing. Cores from different locations—Greenland, Antarctica, and high-altitude glaciers in the Alps and Andes—show similar temporal patterns but varying concentrations. This suggests that nanoplastic pollution has been a hemispheric, if not global, phenomenon for much longer than previously recognized, transported through atmospheric circulation patterns that distribute particles across continents and oceans.

Beyond rewriting pollution history, this research raises important questions about human health. If nanoplastics have been present in the atmosphere for centuries, what might have been their cumulative effect on human populations? Historical medical records might need reexamination in light of these findings, as respiratory and other health issues previously attributed solely to known pollutants like soot or sulfur dioxide might have involved contributions from synthetic nanoparticles.

The ice core nanplastic record also provides crucial context for contemporary plastic pollution efforts. By understanding pre-industrial and industrial revolution levels, scientists can better quantify the unprecedented scale of modern plastic pollution and model its long-term environmental persistence. This historical perspective strengthens the case for urgent action on plastic waste, demonstrating that while plastic pollution isn't exclusively modern, its contemporary scale represents a quantum leap in environmental contamination.

Perhaps most importantly, this research demonstrates the value of looking backward to understand forward. The ice cores remind us that human impact on the planet's fundamental systems began earlier and penetrated deeper than we typically acknowledge. In these ancient frozen archives, we find not just a record of what was, but a warning about what could be—and what we must work to prevent.

As research continues, scientists are expanding ice core drilling operations to additional locations and developing even more sensitive detection methods. Each new core adds another piece to the puzzle of humanity's long relationship with synthetic materials—a relationship that began not with plastic bags and water bottles, but with the first smoky fires of industry that sent invisible synthetic particles spiraling into the atmosphere to be preserved in ice, waiting centuries to tell their story.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025