In a groundbreaking scientific endeavor that reads like the plot of a science fiction novel, researchers have successfully revived ancient microbial communities from the guts of insects preserved in amber for millions of years. The study, focusing on the Eocene epoch, has opened a unprecedented window into a lost microbial world, challenging our understanding of evolution, microbiology, and the very limits of life itself.

The research team, an international collaboration between paleontologists, molecular biologists, and microbiologists, began their work with a collection of exceptionally well-preserved insects encased in Baltic amber, dated to approximately 44 million years ago. Amber, the fossilized resin of ancient trees, is renowned for its ability to create a perfect anoxic, desiccated tomb, preserving specimens in minute detail. While previous studies have extracted and sequenced ancient DNA from such specimens, this project aimed for something far more ambitious: to not just read the genetic blueprints of these microbes, but to actually bring them back to life in a controlled laboratory environment.

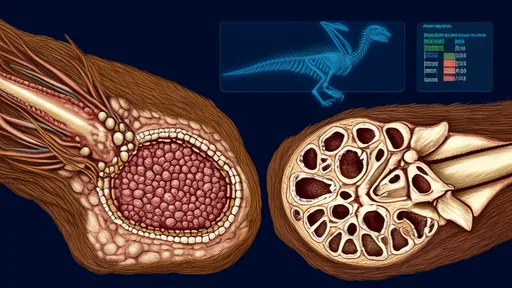

The process was a meticulous dance between extreme caution and cutting-edge technology. Using fine diamond-tipped drills, the scientists carefully extracted minute samples of material from the abdominal cavities of stingless bees and other hymenopterans trapped in the amber. The paramount concern was the exclusion of any modern contaminants. All procedures were conducted in a sterile, positive-pressure cleanroom environment, with researchers wearing full-body suits to prevent the introduction of contemporary bacteria that could sabotage the results. The ancient material was then subjected to a specially designed culture medium, a "soup" of nutrients formulated based on the predicted chemical composition of the Eocene environment and the insect hosts' diet, rich in ancient pollens and saps.

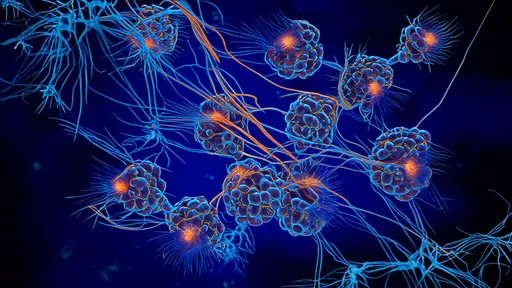

For weeks, the petri dishes showed no activity. Then, slowly, colonies began to form. The resurrection was a success. The team had not isolated a single species, but rather an entire consortium of microorganisms—a snapshot of an ancient gut microbiome, thriving once more. Genomic sequencing confirmed the antiquity of the cultures; their genetic markers were deeply divergent from any known modern lineages, placing them firmly on a separate branch of the tree of life.

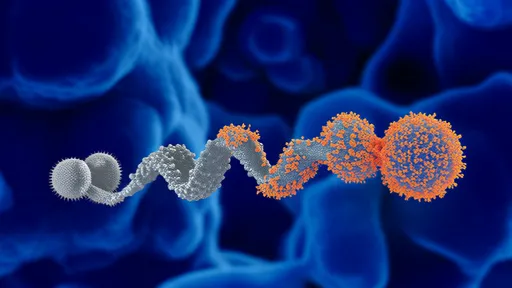

Analysis of this resurrected microbiome has revealed a complex ecosystem with sophisticated functions. The community includes bacteria specializing in the breakdown of complex polysaccharides found in tough ancient plant materials, suggesting a co-evolved relationship that aided the insect host in digestion. Perhaps even more astonishing was the discovery of numerous antimicrobial compounds produced by these ancient microbes. These compounds, which effectively acted as a defense system for the insect's gut, show novel chemical structures unlike any modern antibiotics, offering a potential treasure trove for pharmaceutical research in an age of rising antibiotic resistance.

The implications of this work are profound and far-reaching. Firstly, it shatters the assumption that complex microbial communities cannot survive over geological timescales. This discovery suggests that under perfect preservation conditions, dormancy is not a temporary state but can be an almost indefinite one. Secondly, it provides a direct, functional look at co-evolution. Scientists can now study the interactions between a specific insect host and its gut flora not through inference from DNA fragments, but by observing the living, interacting system, offering unparalleled insights into ancient ecological relationships.

Furthermore, the study opens up an entirely new frontier in the search for novel bioproducts. This ancient microbiome is a biological time capsule, containing molecules and genetic pathways that have been lost to time through extinction. The antimicrobials, enzymes, and other metabolic products discovered could have significant applications in medicine, agriculture, and industry. It represents a new form of biodiscovery, not from remote rainforests or deep-sea vents, but from deep time.

Naturally, the research invites both awe and caution. The idea of resurrecting ancient life forms, even microscopic ones, comes with ethical and safety considerations. The research team emphasizes that all work is conducted under the strictest biosafety level 4 containment protocols. The revived microbes are specialists, adapted to the very specific environment of an insect gut and the warm, greenhouse climate of the Eocene. They are not considered dangerous or likely to survive outside the lab, but the precautionary principle is paramount.

This pioneering work, resurrecting the Eocene insect gut microbiome, is more than a technical marvel; it is a paradigm shift. It moves paleontology from a science of inference based on bones and stones to one of experimental observation. It allows us to test hypotheses about ancient life directly, turning speculation into data. As the techniques are refined, who knows what other lost worlds we might be able to glimpse, one microscopic resurrection at a time. The past, it seems, is not entirely dead—it was merely sleeping, waiting for science to wake it up.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025