For decades, the mysterious ability of migratory birds to navigate across continents with astonishing precision has captivated scientists and laypeople alike. How do creatures like the European robin or the Arctic tern traverse thousands of miles, often through featureless skies or over open ocean, and still find their way? The answer, it turns out, may lie not in conventional biology, but in the strange and counterintuitive world of quantum mechanics. At the heart of this fascinating puzzle is a protein found in the avian eye: cryptochrome.

The story begins with a hypothesis first proposed in the late 1970s: that birds can sense the Earth’s magnetic field. This sense, known as magnetoreception, acts as an internal compass. While the idea was met with initial skepticism, behavioral experiments eventually provided compelling evidence. Birds placed in altered magnetic fields became disoriented; their migratory urge, it seemed, was guided by an invisible force. But the mechanism behind this sense remained elusive for years. Researchers explored various theories, including the presence of magnetic iron minerals in their beaks, but these were ultimately debunked or found to be insufficient to explain the sensitivity and precision of the navigation observed.

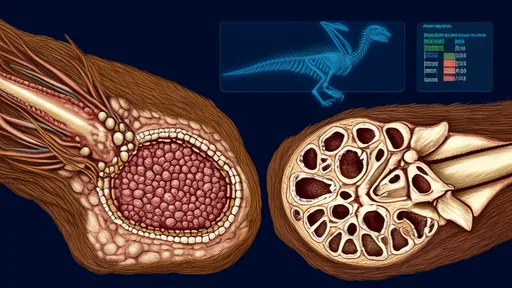

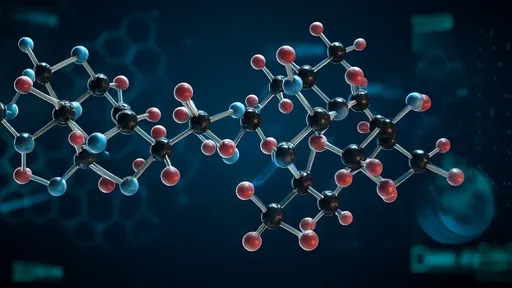

The breakthrough came when scientists turned their attention from the beak to the eye. A light-sensitive protein called cryptochrome, present in the retinas of birds, emerged as the prime candidate. Cryptochromes are a class of flavoproteins that are sensitive to blue light and are involved in regulating circadian rhythms in plants and animals. But in birds, they appear to have taken on an additional, extraordinary function. The theory, now known as the radical pair mechanism, suggests that cryptochrome enables birds to literally see the magnetic field.

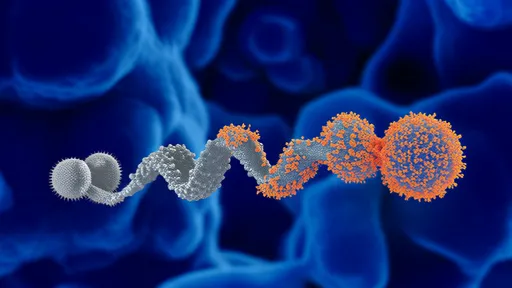

Here is where quantum physics enters the biological stage. The process is believed to start when a photon of blue light hits the cryptochrome protein. This light energy excites an electron, kicking it off on a journey. Within the protein, a pair of electrons become quantum-entangled—their spins linked in a coherent state, meaning the spin of one instantly influences the spin of its partner, regardless of the distance between them. This entangled, coherent pair is what is known as a radical pair. The fate of this radical pair, specifically the chemical products it leads to, is exquisitely sensitive to the direction and intensity of the surrounding magnetic field, most notably the Earth’s.

The Earth's magnetic field is incredibly weak, roughly 100 times weaker than a typical refrigerator magnet. Detecting such a faint signal with a biological system is a monumental task. This is where quantum coherence proves its worth. The quantum-entangled state of the radical pair allows it to act as a supremely sensitive magnetic sensor. The orientation of the bird’s head relative to the magnetic field lines alters the interplay between the spins of the two electrons. This, in turn, affects the outcome of a chemical reaction within the protein, ultimately influencing the nerve signals sent to the bird’s brain. It is hypothesized that this creates a visual overlay—a pattern of light and dark or even color across the bird’s field of vision that shifts as it turns its head, providing a direct and intuitive compass heading.

Maintaining quantum coherence is notoriously difficult. In the warm, wet, and noisy environment of a living cell, quantum states are expected to decohere—to fall apart—almost instantaneously due to interactions with their surroundings. This is the central paradox and the most thrilling aspect of this research. For the radical pair mechanism to work, the quantum coherence within cryptochrome must persist for longer than theory traditionally predicted was possible in biology. Evidence now suggests that this coherence can last for microseconds, which is remarkably long in the quantum world and just enough time for the magnetic sensing chemical reaction to occur. This implies that evolution has engineered a protein that can effectively shield quantum information from its disruptive environment, a concept that was once the sole domain of physicists working in ultra-cold, isolated laboratories.

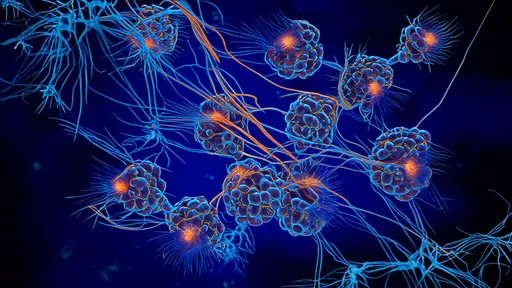

The implications of this discovery ripple far beyond ornithology. The confirmation that quantum effects are not just present but are functionally critical in a biological system shatters the long-held boundary between the quantum and classical worlds. It suggests that nature has been harnessing quantum mechanics for millions of years, long before humans conceived of it. For the field of quantum biology, avian magnetoreception is a flagship example, proving that quantum phenomena like entanglement and coherence can play a role in the macroscopic world of living organisms.

This research also opens up tantalizing possibilities for technology. Understanding how a biological system can protect quantum coherence at room temperature is the holy grail for quantum computing. Engineers struggling to build quantum computers that require expensive and complex cooling systems to near absolute zero could learn invaluable lessons from the humble robin. By studying the structure and function of cryptochrome, we might uncover design principles for novel quantum sensors or even for protecting qubits—the basic units of quantum information—from decoherence, potentially revolutionizing fields from navigation to medicine.

Of course, the story is not yet complete. While the evidence for the cryptochrome-based radical pair mechanism is strong, it remains a compelling model still being refined. Researchers continue to probe the exact structure of the protein in birds, the precise nature of the visual signal perceived, and how this signal is integrated with other navigational cues like star positions, landmarks, and smell. Each experiment brings us closer to fully unraveling one of nature's most exquisite secrets.

The notion that a migrating bird is performing a continuous quantum measurement as it flies south is a breathtaking synthesis of biology and physics. It transforms our understanding of animal navigation and forces us to reconsider the potential of quantum mechanics in the natural world. The next time you see a flock of birds charting a perfect course across the autumn sky, remember: you are witnessing a marvel of evolution, a living testament to the fact that the quantum and the classical are not separate realms, but are intimately, and beautifully, intertwined.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025