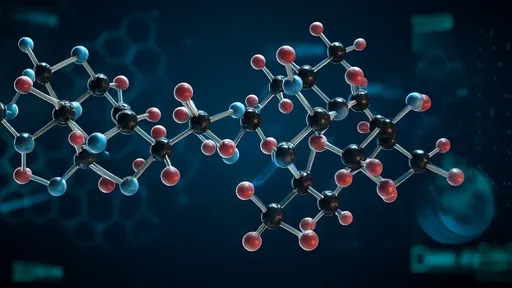

In an era where digital data generation is exploding at an unprecedented rate, scientists and technologists are looking toward an ancient and fundamental molecule—DNA—for solutions. DNA, the very blueprint of life, is emerging as a revolutionary medium for long-term, high-density data storage. The concept of DNA-based data archiving is no longer confined to theoretical discussions or science fiction; it is rapidly evolving into a tangible, global initiative aimed at preserving humanity’s most valuable information for centuries, if not millennia, to come.

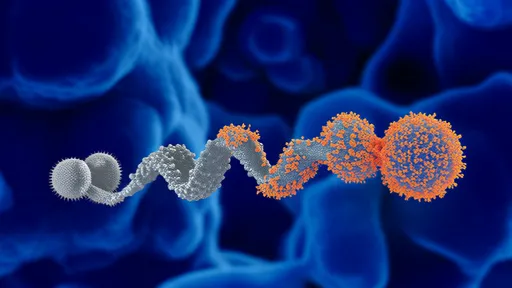

The core idea behind DNA data storage is both elegant and profound. Digital data, which is traditionally stored as sequences of 0s and 1s on magnetic or optical media, is instead encoded into the four nucleotide bases of DNA: adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T). Through sophisticated algorithms, strings of binary code are translated into custom-designed synthetic DNA strands. These strands can then be synthesized, stored, and later sequenced to retrieve the original information. The density of DNA storage is staggering; it is estimated that all the world’s data could theoretically fit into a container the size of a few sugar cubes.

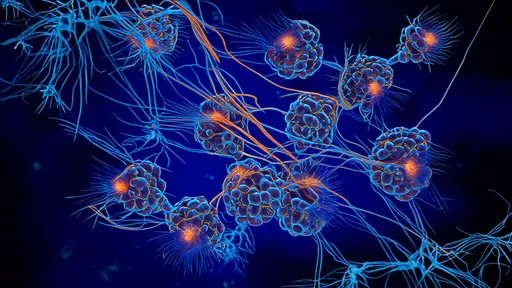

However, the vision extends far beyond mere storage density. The true power of this technology lies in its potential for creating a global, encrypted biological data repository. This is not just a backup solution; it is a secure, decentralized, and incredibly durable archive. Imagine a future where humanity’s collective knowledge—scientific discoveries, cultural heritage, historical records, and even personal genomic data—is preserved in these molecular vaults, safeguarded against digital obsolescence, natural disasters, or societal collapse.

The architecture of such a global system is multifaceted. It begins with the encoding process, where data is not only translated into DNA sequences but also packaged with robust error-correction codes. These codes are essential because the synthesis and sequencing of DNA are not flawless processes; they can introduce errors. Advanced algorithms, often inspired by those used in quantum computing or deep space communication, are employed to ensure data integrity, allowing for perfect reconstruction of the original files even if the DNA strand is partially damaged or degraded over time.

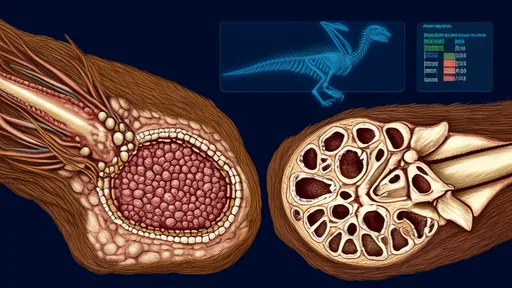

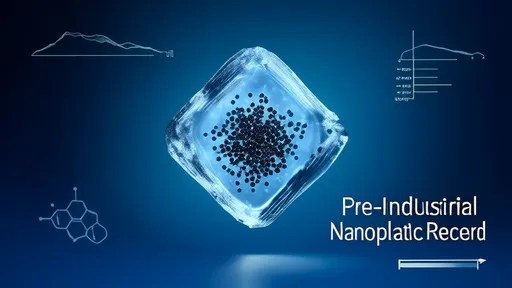

Once encoded, the DNA must be synthesized. This is currently one of the most expensive steps, but costs are plummeting thanks to advancements in biotechnology. Companies are developing automated, high-throughput platforms that can write vast amounts of data into DNA at accelerating speeds. The synthesized DNA is then not stored in a living cell, which could mutate or replicate unpredictably, but is instead dehydrated and encapsulated in inert materials like silica glass. These tiny capsules protect the DNA from moisture, oxygen, and UV radiation, creating a time capsule that can remain stable for thousands of years under cool, dry conditions—far outlasting any hard drive or magnetic tape.

The global aspect introduces the need for a distributed physical infrastructure. Rather than a single, vulnerable location, a network of secure, climate-controlled vaults would be established around the world. These could be located in geologically stable regions, deep underground mines, or even in arctic permafrost, mimicking the Svalbard Global Seed Vault but for digital-preservation. This redundancy ensures that the loss of one facility would not mean the loss of the data it contains.

Perhaps the most critical component of this entire system is encryption. Storing the world's most sensitive data—from government documents to private health records—in a biological format necessitates an unprecedented level of security. The encryption protocols for DNA data storage are a hybrid marvel, combining classical cryptographic techniques with the unique properties of biology. Data can be encrypted before it is even translated into a DNA sequence. Furthermore, the physical DNA itself can be secured. For instance, without the specific primer molecules required for polymerase chain reaction (PCR)—a key step in sequencing—the data-containing DNA is just a meaningless molecule, a biological lock without its key.

Access and retrieval form another layer of the system. To read the data, a sample of the DNA would be sequenced, a process that is becoming faster and cheaper every year. The resulting string of A's, C's, G's, and T's is then fed into a decoder, which reverses the initial encoding process, checks for and corrects errors using the built-in correction codes, and finally outputs the original digital file. This entire pipeline—from physical tube to usable data—could be automated within secure facilities, with access governed by multi-factor authentication and blockchain-based logging to create an immutable record of who accessed what data and when.

The implications of a functional global DNA data repository are profound. For governments and international bodies, it offers a way to preserve critical infrastructure blueprints and legal documents for future generations. For research institutions, it provides a permanent home for massive datasets from particle physics to astronomy, which are currently too large and expensive to store indefinitely on conventional media. For libraries and museums, it is a chance to etch the entirety of human culture—every book, song, and painting—into a medium that could survive even if our digital civilization does not.

Of course, significant challenges remain. The cost, while falling, is still prohibitive for widespread adoption. The write (synthesize) and read (sequence) speeds, though improving, are not yet competitive with electronic systems for daily use. There are also ethical and philosophical questions to grapple with: Who owns this data? Who decides what is archived? How do we prevent the creation of a biological black market for encrypted data? The development of this technology must be accompanied by a robust international legal and ethical framework.

Despite these hurdles, the momentum is undeniable. Major technology corporations, biotech startups, and university research labs are investing heavily in overcoming these obstacles. The goal is not to replace your cloud storage or laptop hard drive, but to create a complementary, ultra-long-term cold storage solution for information that we simply cannot afford to lose. The DNA molecule, which has preserved the information for building life for billions of years, may now be tasked with an even greater responsibility: preserving the memory of civilization itself.

This is not a distant future prospect. Pilot projects have already successfully stored everything from entire operating systems and classic films to scientific papers in DNA. The next decade will likely see the construction of the first prototype large-scale archives. We are standing at the precipice of a new era in information technology, one where biology and digitality converge to create a legacy that can truly stand the test of time.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025