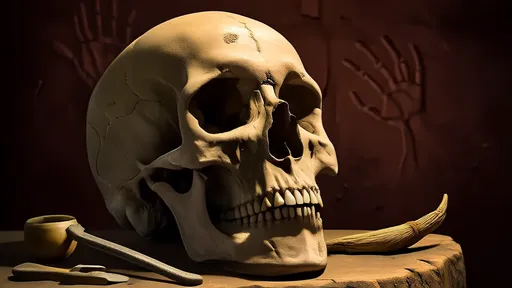

In the collective imagination, Neanderthals have long been portrayed as primitive brutes, a simplistic caricature that modern science continues to systematically dismantle. The latest evidence challenging this outdated view comes not from a grand cave painting or a sophisticated tool, but from something remarkably intimate: a 50,000-year-old tooth. Analysis of dental calculus—the hardened plaque—from a Neanderthal individual found in the Cova de les Teixoneres site in Spain has revealed a startling chapter in prehistory: the practice of intentional, plant-based medicinal dentistry. This discovery provides the earliest known chemical evidence of a form of oral healthcare, suggesting a level of empathy, knowledge, and cultural sophistication previously denied to our ancient cousins.

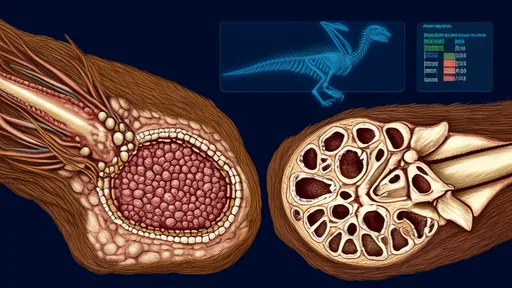

The key to this discovery lies in the microscopic world preserved within calcified plaque. Dental calculus acts as a biological time capsule, trapping and preserving a wealth of materials an individual inhaled or consumed, including starch granules, plant fibers, and phytochemicals. By applying advanced analytical techniques like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry to samples from the Neanderthal molar, researchers were able to detect and identify specific organic compounds locked away for millennia. The findings pointed unequivocally to the consumption of plants from the Asteraceae family, commonly known as the daisy or sunflower family, not for nutritional purposes, but for their well-documented medicinal properties.

The individual in question, analysis suggests, was suffering from a significant dental abscess, a painful infection at the root of the tooth, as well as a chronic gastrointestinal parasite. The plant chemicals identified, including bitter-tasting and anti-inflammatory compounds, are known for their analgesic and antibacterial qualities. The choice of these specific plants, which offer little nutritional value and have a notably unpalatable taste, strongly indicates a deliberate attempt to treat the symptoms. This was not a case of simply eating whatever was available; it was a targeted selection of natural pharmacopeia to alleviate pain and fight infection. It represents a clear cognitive leap from mere subsistence to an applied understanding of the therapeutic properties of the local environment.

This act of self-medication, or perhaps even care provided by a group member, profoundly alters our perception of Neanderthal social behavior. The capacity for empathy—the recognition of suffering in another and the motivation to alleviate it—is a cornerstone of complex social structures. A severely ill individual with dental pain and parasites would have been a liability to a hunter-gatherer group, struggling to chew tough food and keep pace. The intentional administration of medicine suggests a community that valued its members enough to provide supportive care, knowledge sharing, and perhaps even palliative support, ensuring the survival and well-being of the group as a whole. This moves far beyond the simplistic "survival of the fittest" model and hints at a society capable of compassion and collective care.

Furthermore, this discovery places Neanderthals firmly within a tradition of ethno-botanical knowledge that was once thought to be the exclusive domain of Homo sapiens. The ability to identify, remember, and utilize specific plants for their non-nutritive, chemical effects requires advanced cognitive abilities. It involves observation, pattern recognition, and the cultural transmission of knowledge across generations. This isn't merely instinct; it is the foundation of medicine. It suggests that Neanderthals possessed a sophisticated understanding of their ecosystem, categorizing flora not just as food or fuel, but as sources of healing. This cognitive framework is a significant indicator of complex thought processes and cultural depth.

The implications of this finding extend beyond a single tooth or a single individual. It forces a broader re-evaluation of Neanderthal capabilities. If they were engaged in palliative care and plant-based medicine 50,000 years ago, what other aspects of their behavior have we underestimated? This evidence dovetails with other discoveries that point to symbolic behavior, such as the use of pigments, potential engraving, and cave structures. Together, they paint a picture of a people who were behaviorally modern in many respects, with rich cultural practices and complex social interactions. The boundary between Neanderthals and modern humans becomes increasingly blurred, suggesting that the cognitive seeds of culture, medicine, and compassion were present in a common ancestor long before our species walked the Earth.

In conclusion, the chemical evidence gleaned from ancient Neanderthal dental calculus is a powerful testament to their humanity. It reveals a story of pain, knowledge, and likely, compassion. It shows us a people who were not just struggling to survive, but were actively engaged in improving their quality of life through an understanding of nature's pharmacy. This tiny, calcified sample does more than just rewrite a paragraph in a textbook; it fundamentally challenges a long-held hierarchy that placed our species on a pedestal of cognitive uniqueness. The Neanderthal, it seems, was not a simple brute, but a knowledgeable healer, a caring community member, and a sophisticated human who looked at a bitter plant and saw not just food, but relief.

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025

By /Aug 25, 2025